Nevada’s Water Smart Program (Cont’d.)

After researching the Nevada Assembly Bill 356, which prohibits the use of Colorado River water to irrigate non-functional grass (see October 24 LWS Blog), I was struck by the statement to the Associated Press by Nevada Assemblyman Howard Watts III, a sponsor of the bill who said:

“This sends a clear message about what other states need to be looking at in order to preserve water.”

I wondered what water conservation would look like in northern Colorado, where I live. The Colorado State University Extension (CSUE) published a fact sheet on water conservation in and around the home (CSUE, 2014) containing household water use estimates. Water uses were categorized into bathroom, kitchen, miscellaneous (e.g., car washing) and lawn care, with breakdowns of uses in gallons, for typical activities. The estimates included usage for non-water- efficient and water-efficient appliances and landscaping.

Indoor efficiency considers not only whether updated appliances and flow-controlled plumbing fixtures are being used but also our personal choices. For example, running a dishwasher only when it is full, shorter showers, and turning off the faucet while brushing teeth can save hundreds, if not a thousand, gallons per month. Outdoor irrigation efficiency includes landscaping choices (drip vs. sprinkler irrigation and drought tolerant vs water-loving foliage), but also includes the choice to not over-irrigate or irrigate over paved surfaces.

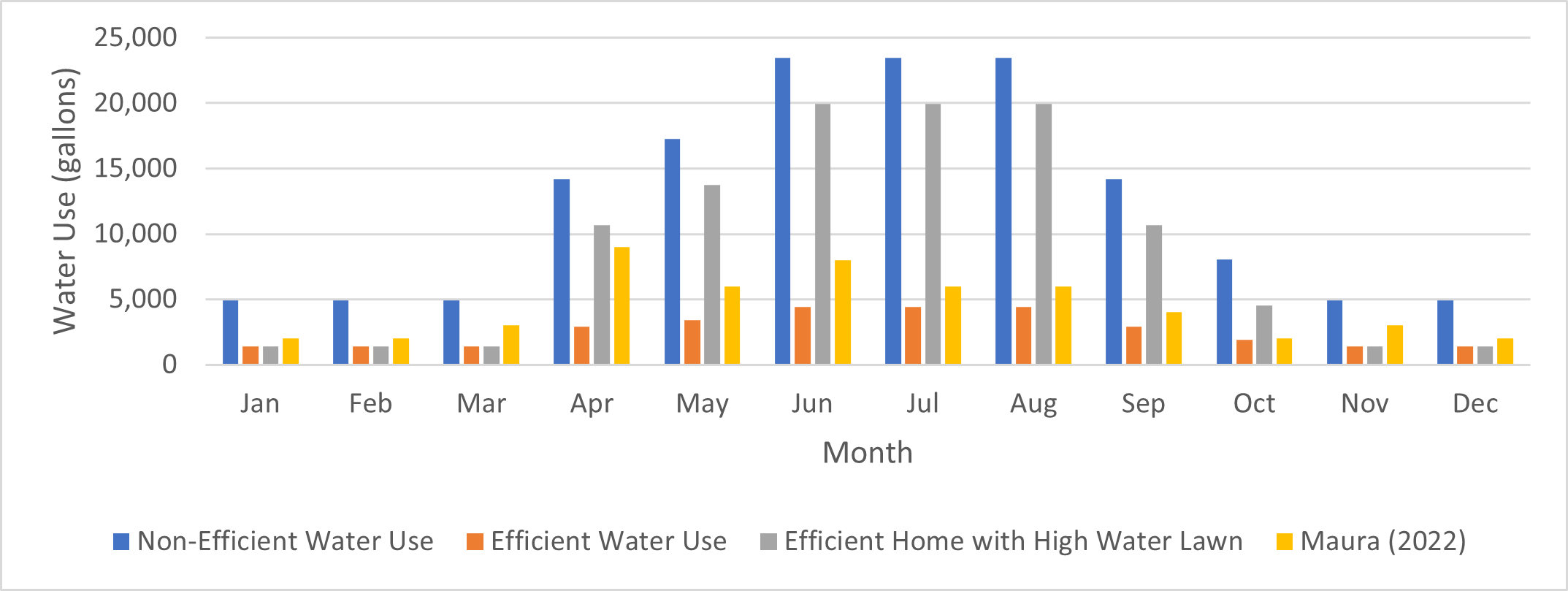

Figure 1 is an estimate of monthly household indoor and outdoor water use based on the CSUE fact sheet and my own meter-based water use. The maximum and minimum values were plotted for non-water-efficient estimates (in blue) and water-efficient estimates (in orange) for both indoor and outdoor water uses. A comparison of blue and orange bars illustrates that water-efficiency could save up to 71 to 81 percent over the non-efficient uses. Also plotted in Figure 1 (in gray) are the water use estimates for a household with indoor water use efficiencies but with outdoor non-water-efficient Kentucky blue grass. A comparison of the gray and orange bars illustrates that if only indoor water-efficiency is practiced and outdoor water use efficiency is not practiced, the outdoor non-efficient landscaping could use up to 57 to 78 percent more water than an indoor and outdoor water-efficient household.

Figure 1: Residential Water Use in Northern Colorado (CSUE, 2014)

Curiosity about where my own household fits into these estimates led me to plot my 2022 water use on the graphs for comparison (gold). Although I have a fairly water efficient, 2-person household, my small lawn and garden consume up to 75 percent of my mid-summer water use.

The town where I live does restrict residential lawn irrigation to 3-days per week between the hours of 6 pm to 10 am and prohibits runoff into gutters and washing of paved areas. Even so, I can see that my neighbors and I could realize a significant water savings by water-efficient landscaping. For the past decade or more my town has offered residents a low-cost “garden in a box” comprised of native flowering plants. In the summer of 2023, it launched a demonstration project by removing non-functional lawns around city buildings and replacing them with water-efficient landscaping. The town is avidly promoting outdoor water efficiency because it, like other water-purveying entities in Colorado, have a finite amount of water each year that is based on the amount of its water right. This is analogous to the limits on the Colorado River use by the Southern Nevada Water Authority (“SNWA”), discussed in our previous blog.

Therefore, it makes sense to me that the water budget of a town or region be based on practical and efficient uses of water, and inefficient uses, however tempting due to their visual appeal, should be discouraged through limiting water use via various means, including tiered water pricing schedules, limitations on the amount and type of outdoor landscaping, planting of native plants, xeriscaping, irrigation methods, timing of irrigation, etc. It is also clear to me (based on Figure 1) that managing outdoor water is the fastest way to reducing overall water use as it can represent the majority of overall water use, as my home outdoor water use consumed approximately three quarters of all the water I used in a year.

If you have any water resources issues, LWS can help; please contact us for help at 303-350-4090 or by email.

Maura Metheny, Ph.D., P.G.: maura@lytlewater.com

Bruce Lytle, P.E.: bruce@lytlewater.com

Anna Elgqvist, EI: anna@lytlewater.com

Subscribe to LWS blogs HERE!

References Reviewed

CSU Extension, 2014. Water Conservation In and Around the Home. Fact sheet 9.952. (Available at https://extension.colostate.edu/topic-areas/family-home-consumer/water-conservation-in-and-around-the-home-9-952/).

National Geographic, 2023. National Geographic Education Resource. (Available at https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/conservation/).